Priceless Anzio Insight: Mauldin's War Comics, Memoir

WWII cartoonist hit front lines with the Force, other units

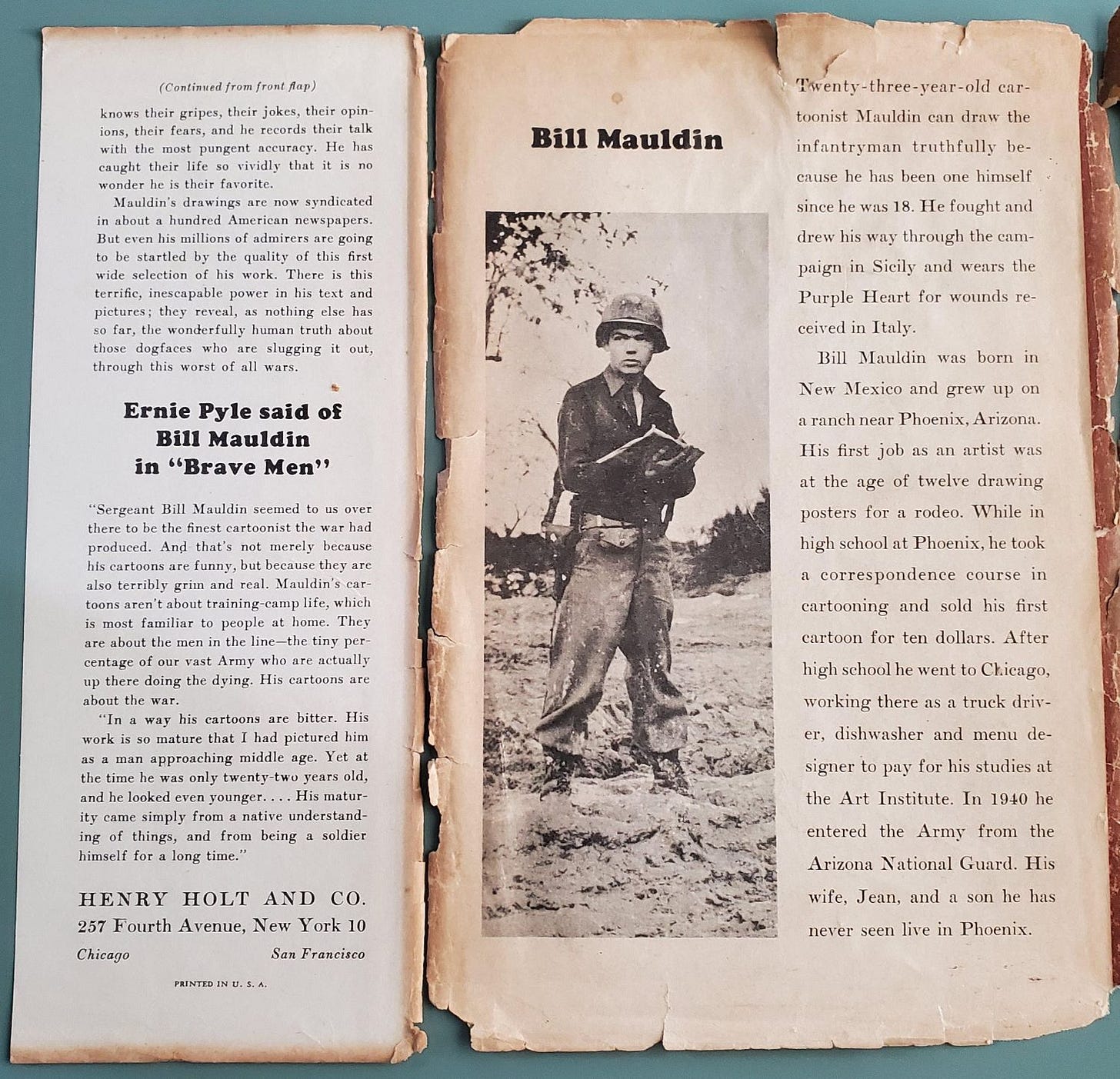

I wrote about Erick, my father, in my book about WWII in Italy, but there are many more-well-known figures from that time and place, including two who were not even alive, and one who went around drawing pictures.

Willie and Joe were the creation of cartoonist Bill Mauldin, who served in the same theater of war as my father. It’s conceivable that Erick could have met Bill and watched him sketch.

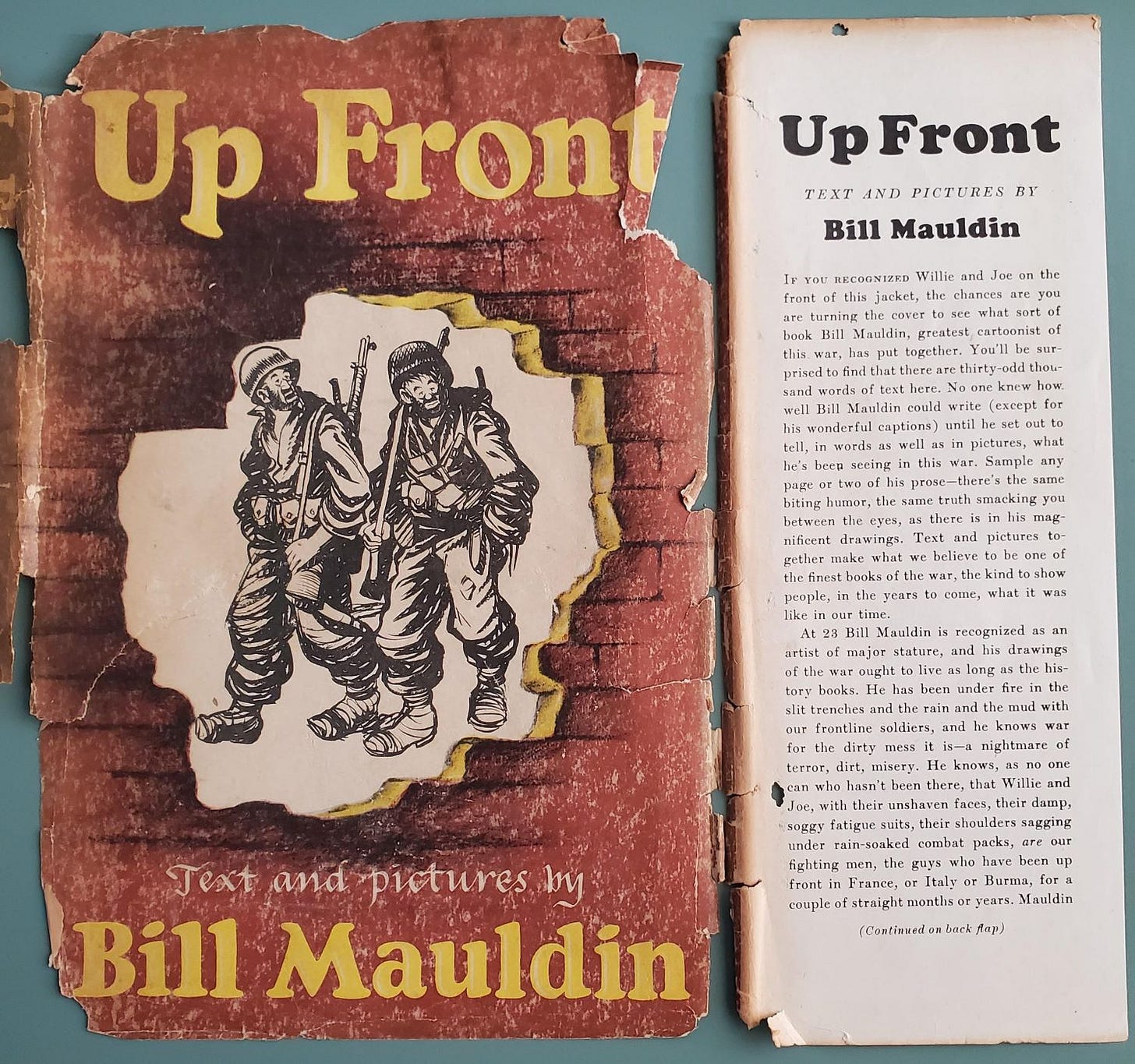

So when I happened upon a $1 slim hardbound book at an estate sale recently (oh, how I do love estate sales), its faded dust jacket nearly disintegrating in my hands, I knew that I’d found a treasure. Other than the jacket, this 1945 first edition was in a condition used booksellers would call very good. I thought I’d struck gold.

“Up Front” is Mauldin’s narrative account—his memoir, if you will—of his time in the trenches and on the move with the American troops in Italy. His observations of what the soldiers went through feel honest, personal and accurate.

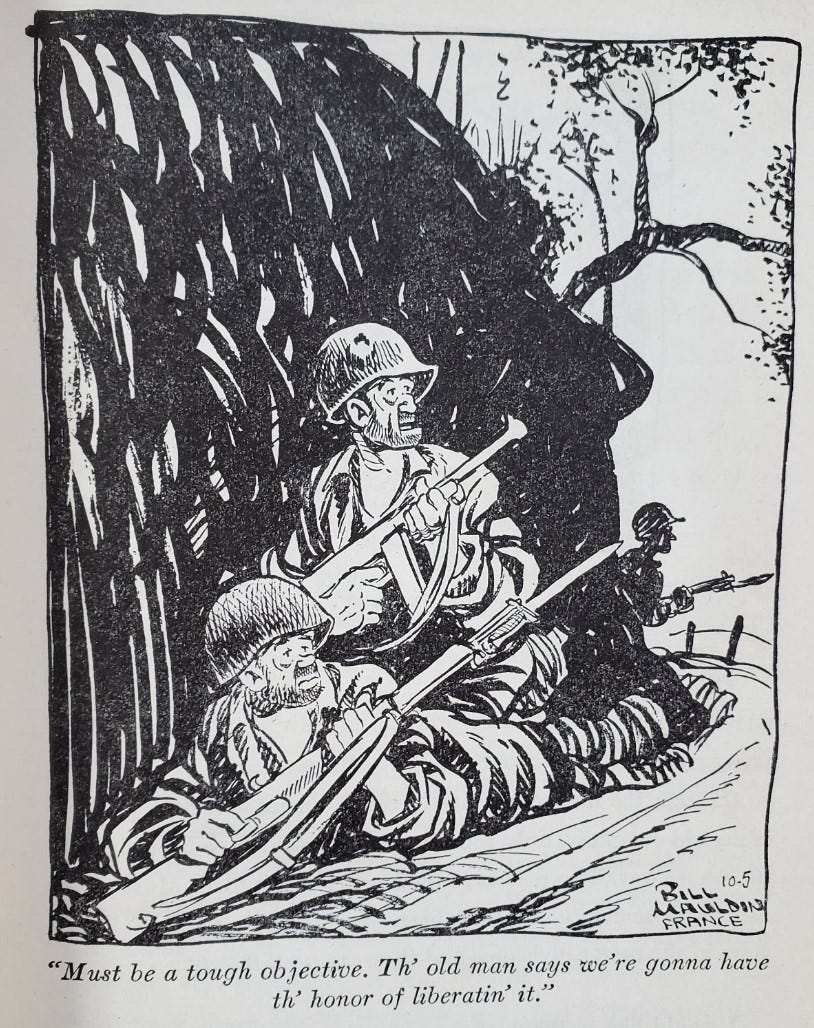

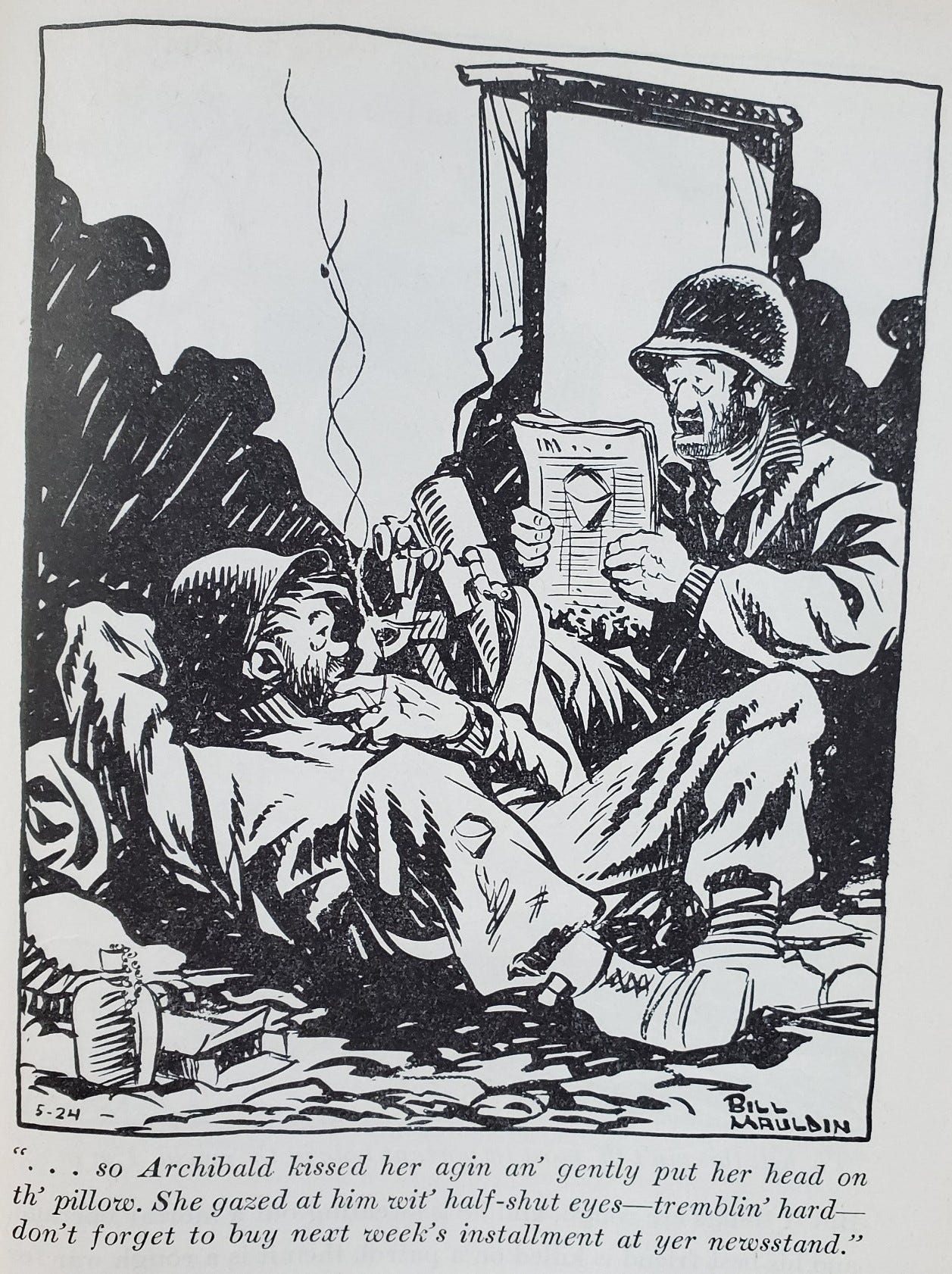

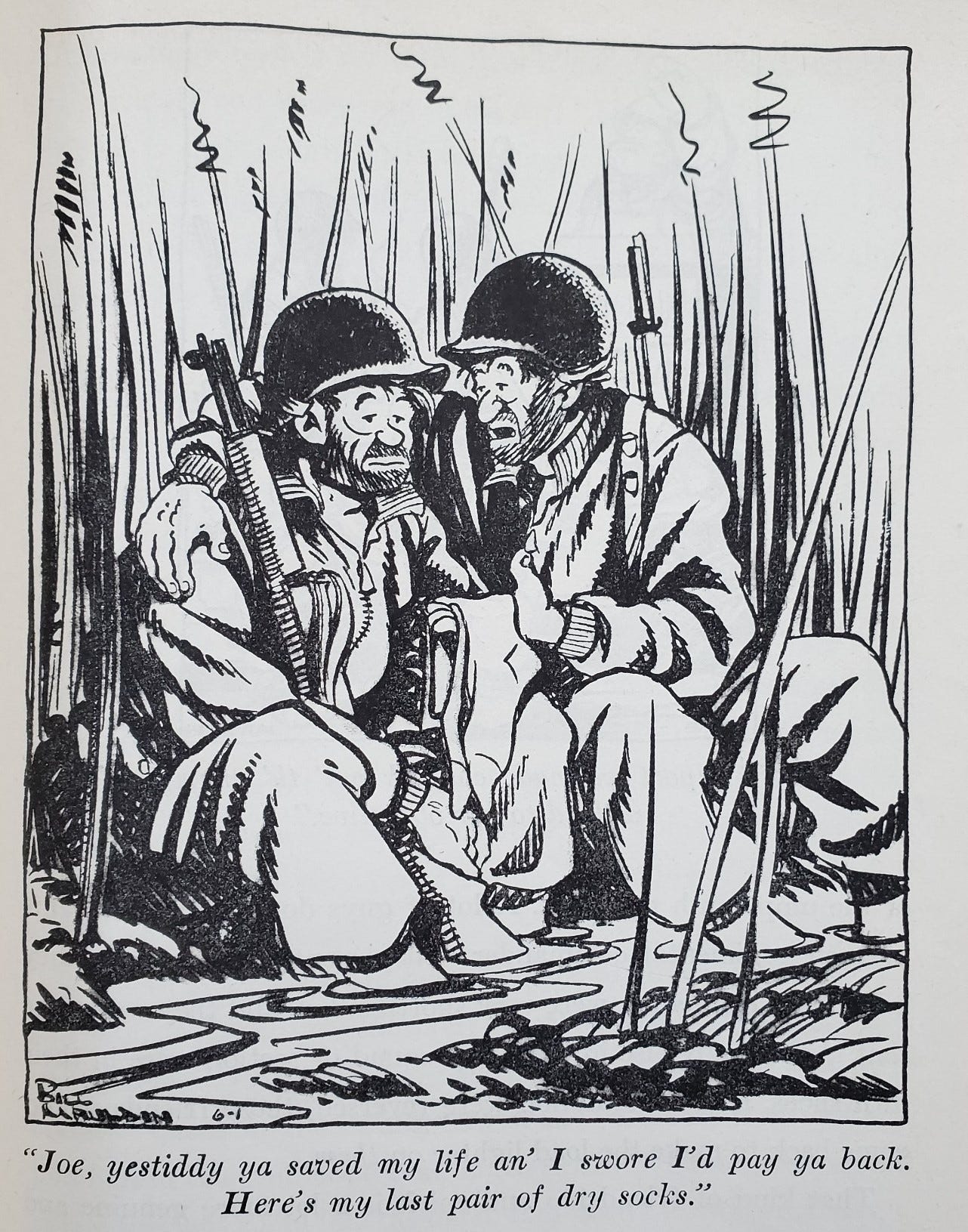

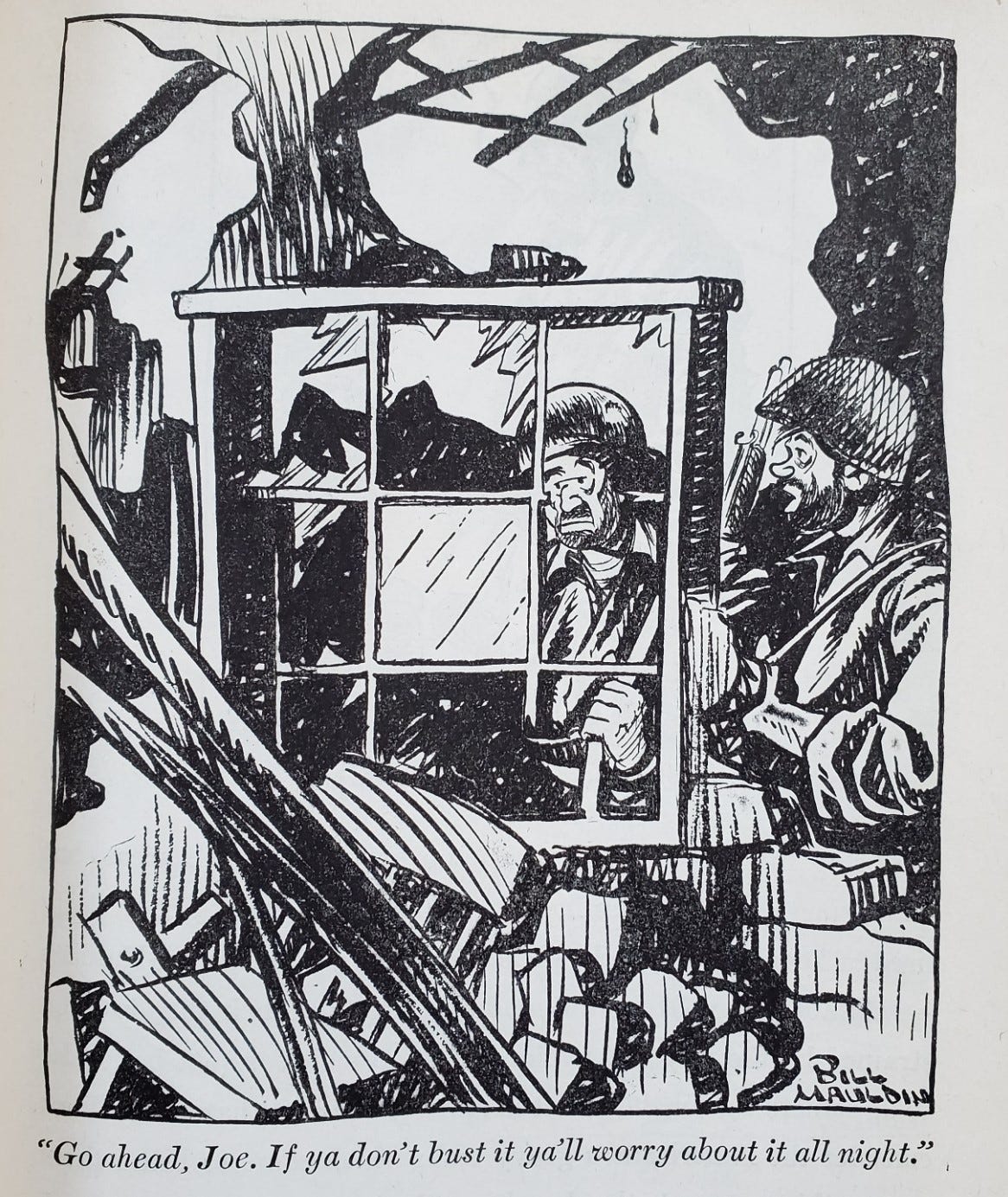

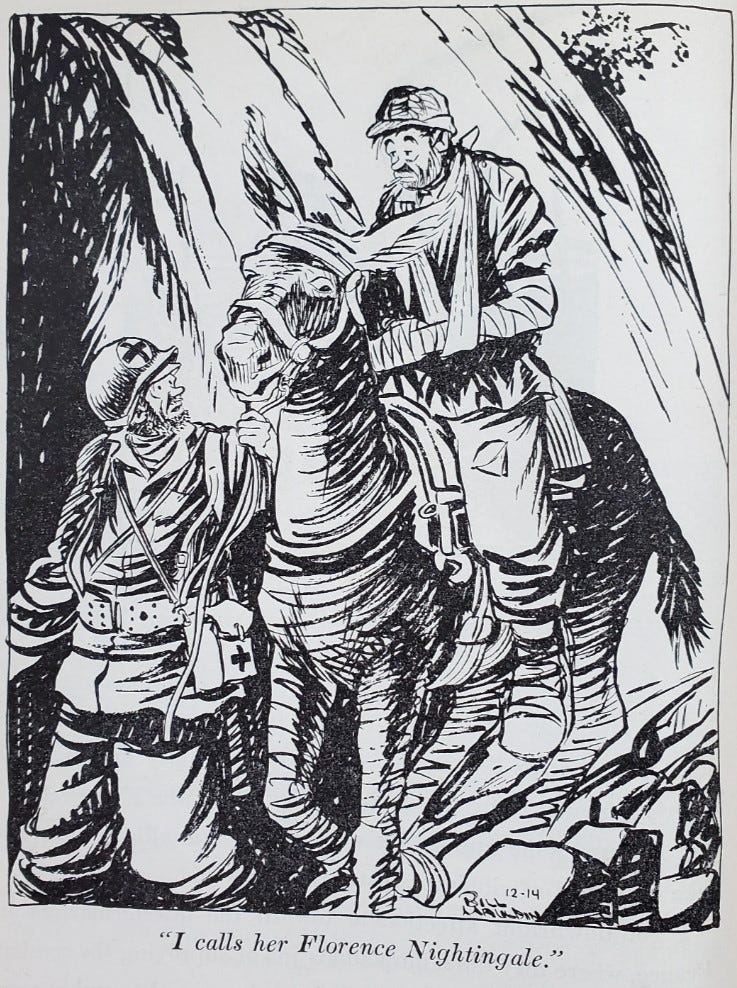

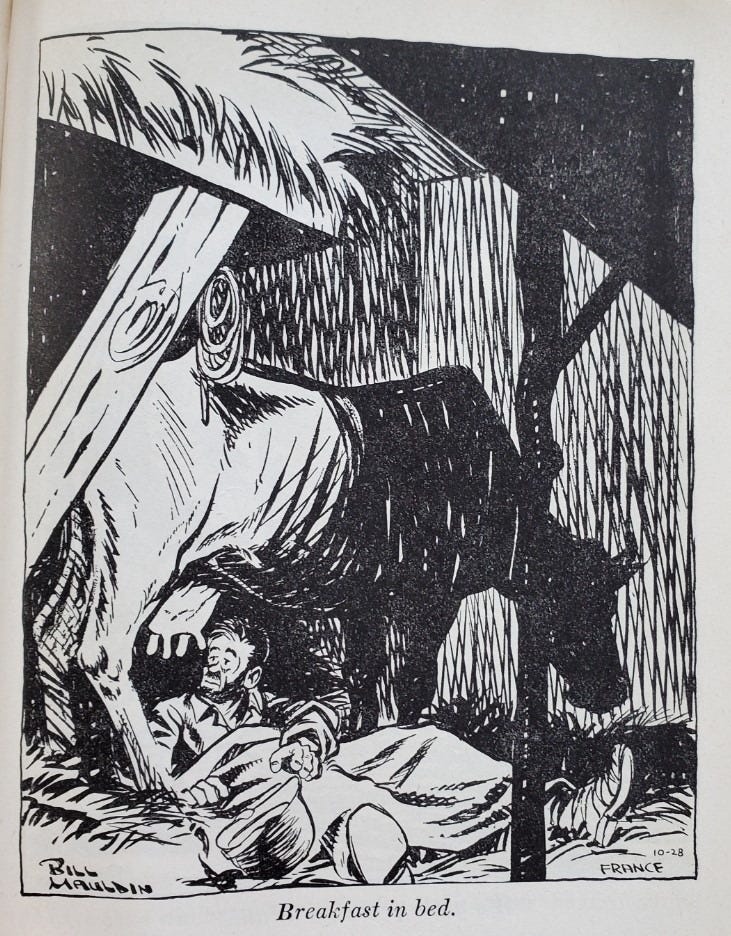

The stories also provide explanations of the resulting cartoons, which were printed in military newspapers but also syndicated into hundreds of papers back home. Plenty of those wonderful single-panel comics also appear in the book, and I will share a few here.

Mauldin explains his perspective, saying he’s young and inexperienced (he was 22 when he arrived at Anzio), so he doesn’t “try to picture this war in a big, broad-minded way.” Instead, he focuses on the infantry (“dogfaces” or “doggies” in his parlance) and tries to find humorous situations in their plight. However, he writes, “maybe I can be funny after the war, but nobody who has seen this war can be cute about it while it’s going on.”

The cartoons, he hopes, give glimpses to the folks at home about how the war is affecting the soldiers. “They need people telling about them so that they [the soldiers] will be taken back into their civilian lives and given a chance to be themselves again.”

Willie and Joe represented the soldiers on the line, for whom “[l]ife is stripped down to bare essentials,” he writes. That will change a man in ways that only his fellow doggies would understand. Still, he says:

“Perhaps he will change back again when he returns, but never completely. If he is lucky, his memory of those sharp, bitter days will fade over the years into a hazy recollection of a period which was filled with homesickness and horror and dread and monotony, occasionally lifted and lighted by the gentle, humorous, and sometimes downright funny things that always go along with misery.”

The cartoonist got hit by a mortar fragment on a deployment with a mountain-fighting unit (not wanting to play favorites he doesn’t name units, but I see Dad’s unit, the First Special Service Force, in some of his accounts), which resulted in the comical farce of men climbing a steep, rocky hillside and their sergeant yelling “Hit th’ dirt boys!”

He recalls that “the only thing that saved me from most of the mortar shells was the fact that sliding down the hill made me as parallel to the earth as if I had been lying horizontally. Many hundreds weren’t so lucky on the mountainsides.” He could have been writing about the Force’s 70-degree climb up Monte la Difensa, my dad’s first big battle.

Describing the “miserable” mountain fighting in Italy, he outlines the effect on the men: “those men have seen actual war first hand, seeing their buddies killed day after day, trying to tell themselves that they are different—they won’t get it; but knowing deep inside them that they can get it—those guys know what real weariness of body, brain, and soul can be.”

One of Mauldin’s stories relates directly to a story my dad told my mom in a letter from his hospital bed, which I recount in my book. On night patrol, they snuck up on an occupied farmhouse where the Germans were having a “spree” and playing the popular song Lili Marlene, made famous by Marlene Dietrich. The patrol came away with prisoners.

“Our musical geniuses at home never did get around to working up a good, honest, acceptable war song, and so they forced us to share Lili Marlene with the enemy,” he writes. His cartoon could have resulted from hearing that story from my dad’s platoon.

He uses the derogatory term “kraut” in the caption. The demeaning nickname was shortened from the cabbage dish sauerkraut. Mauldin also notes it as the most common term for Germans used by our soldiers, much more than Nazis, as a distinction between the average German drafted into the war versus those who joined the Nazi Party.

Another story that my father told, I’m sure reluctantly, was about losing soldiers on each side of him in the initial Monte la Difensa battle, and Mauldin offers his perspective on that too. “When you lose a friend you have an overpowering desire to go back home and yell in everybody’s ear, ‘This guy was killed fighting for you. Don’t forget him—ever.”

At Anzio, Mauldin lost a friend, Gregor Duncan, “one of the finest and most promising artists I’ve ever known,” and he observes that “it’s a pretty tough kick in the stomach when you realize what people like Greg could have done if they had lived. It’s one of the costs of the war we don’t often consider.”

So, too, must a soldier carry strong feelings toward the men around him who help him stay alive.

One of my siblings told a story of one of Dad’s old Army buddies coming to visit us on the farm. As my sibling stood next to where he was sitting at the kitchen table, he took a knife off the table and said something like “You want to know what your dad did to me?” and jammed the knife into his leg. The shocked kid then heard how Dad had saved that man’s life, even though the guy lost a leg and now had a wooden one. You don’t forget heroism, friendship or situations like that.

Besides depicting the life of the soldiers, Mauldin showed what it looked like in the places they fought, and he discusses the bombed-out towns he saw and sketched.

“There’s something very ghostlike about a wall standing in the moonlight in the midst of a pile of broken rubble and staring at you with its single unblinking eye, where a window used to be. There’s an awful lot of that in Italy, and it’s going to haunt those people for years.”

Nowhere was that more apparent to me than in San Pietro Infine, a village I describe in the book. It was so badly wrecked that the townspeople just decided to abandon it and build a new town farther down the hill. Today the ruins are a national monument.

Seeing Mauldin’s touching drawing of a wounded man on a mule, I thought again of my dad. I believe Erick was evacuated on the back of a mule twice. The first was when he contracted jaundice after the fight for Mount Majo and had to be sent back for medical care. The second time was after he was cut down in the final Anzio push—his last battle—and family lore has it that he was evacuated to the Army triage site by locals who hoisted him on the back of a mule.

Perhaps the most visceral description of what it was like to be a doggie in that war in Italy came from Mauldin’s suggestion of doing a home experiment:

“Dig a hole in your back yard while it is raining. Sit in the hole until the water climbs up around your ankles. Pour cold mud down your shirt collar. Sit there for forty-eight hours, and, so there is no danger of your dozing off, imagine that a guy is sneaking around waiting for a chance to club you on the head or set your house on fire.

“Get out of the hole, fill a suitcase full of rocks, pick it up, put a shotgun in your other hand, and walk on the muddiest road you can find. Fall flat on your face every few minutes as you imagine big meteors streaking down to sock you.

“After ten or twelve miles (remember, you are still carrying the shotgun and the suitcase) start sneaking through the wet brush. Imagine that somebody has booby-trapped your route with rattlesnakes which will bite you if you step on them. Give some friend a rifle and have him blast in your direction once in a while.

“Snoop around until you find a bull. Try to figure out a way to sneak around him without letting him see you. When he does see you, run like hell all the way back to your hole in the back yard, drop the suitcase and shotgun, and get in.

“If you repeat this performance every three days for several months you may begin to understand why the infantryman sometimes gets out of breath. But you still won’t understand how he feels when things get tough.”

Boy, that Bill Mauldin was a card, eh? In passages like that, his ability to get you to feel the war from the perspective of the dogface was almost as good as his cartoons, which were aces.

One final scene he describes that I’ll put in the “probably the Force” category was about a fishing technique practiced by some soldiers: “One American-Canadian division had a neat system for supplementing their GI chow at Anzio. They dug up German anti-tank mines, wired them electrically, dropped them into the sea, exploded them and then harvested bushels of fish.

“Such highly unorthodox but extremely effective methods of supply persuaded the Germans—fearful, perhaps, that having exhausted all available sources of provision, the dogfaces would turn to cannibalism—to keep a respectfully wide No Man’s Land between their lines and our own. The boys took advantage of this and used to run down rabbits and chickens far ahead of our forward machine-gun positions.”

And cows. I know the Force had a herd.

I wish my dad had been able to tell me such stories, not about the fighting but about the mundane daily life of a dogface. The ridiculous situations. The gallows humor. The inseparable buddies. I hope he carried those with him to offset the painful memories of the horrible work.

Ah well. At least I have Mauldin.

Get a signed (even pesonalized) copy of my book “All Roads Lead to Rome: Searching for the End of My Father’s War,” sent directly to you from my neighborhood bookshop.

I remember those comics. Not sure where I saw them. Mom and dad did take The Williston Herald, but I can’t believe they were in there. I don’t remember reading his book, but many of the comics you reprinted are ones I’ve seen. Planning on reading your book. Just not right now. Great read. We forget too much.