An element of my father’s story addressed just briefly in All Roads Lead to Rome was the presence of a Force member who came from a far distant shore to be part of the commando unit. The First Special Service Force was an international team comprised of Americans and Canadians…and one Norwegian.

On a recent trip to Norway to visit family (more on this “reverse immigration” in another Substack soon), I had a chance to renew my friendship with that Norwegian Forceman’s nephew and also learn much about Norway’s situation during the war. I want to share what I learned on my travels.

Norway was, after all, the initial reason that the Force had come into existence.

The original plan was to drop a highly trained unit of paratrooper commandos into the mountains of Norway. They would ski down to engage the Germans. The Nazis had invaded Norway and, as an occupying power, had commandeered Norway’s industrial capacity, such as production of iron ore to make steel, to fuel their war machine.

The Allies were particularly concerned about a heavy water hydroelectric plant in the mountains near Rjukan whose product, also known as deuterium, was an ingredient that could be used for production of an atomic bomb. They couldn’t let the Germans beat them in development of that crucial weapon.

And so, the audacious plan got a hearing from British leaders, who promoted it to American leaders, and they set about to form the Force.

As my dad was undergoing basic training, a team from the Pentagon had been tasked with recruiting new soldiers who could be trained for this job. Under the direction of Colonel Robert T. Frederick, acting on orders of his boss General Dwight D. Eisenhower, men were sought through a survey of West Coast bases. Erick was at a base in the San Francisco Bay area, and his C.O. put him on the list to be interviewed.

In my research I came upon two coincidences, which is always delightful: Dad was training at the same base where Frederick had trained a few years previously. Also, the man who was to become the lone Norwegian in the Force, Finn Roll, had made his way to his uncle’s home in the Bay Area when he arrived in the U.S. and had enlisted in our army there. By the time my dad was there, Finn was stationed in D.C., but from all the way across the country he would be recruited to the Force too.

So my father, son of an immigrant from Norway, was destined to meet Finn, surely Norway’s most recent immigrant, at the Force training base in Helena, Montana.

Finn’s story, as first told to me by his affable nephew Jan Roll when I met him at a Force event in Italy, was incredible. Finn was itching to take on the Germans who were making life hell for his country, but he was so young that the Norwegian resistance movement turned him down. Not to be thwarted, he and a buddy slipped away one night in a small boat, which they, incredibly, sailed to England. From there, Finn made his way to America, found his uncle, and joined the U.S. Army.

But he ultimately would be thwarted from fighting in Norway, as the invasion plan was dropped before the Force had finished their training. The plot was deemed to be a suicide mission, and the Allied commanders did not want to immediately lose this new, highly trained unit. Finn would go with the Force to fight in Italy and beyond.

Back in his homeland, while Finn was becoming a Forceman, the Norwegian resistance movement was well underway. (Finally, I am getting to the point of this story, which is what I learned on my recent trip. Sorry for all the background, but I wanted to show the context.)

At the Norges Hjemmefrontmuseum, also known as the Home Front Museum or the Resistance Museum, I learned the story of what Finn’s countrymen and -women were doing to battle the occupiers. The museum sits in a 13th century fortress on a bluff overlooking Oslo’s bustling harbor.

Making an unmistakable statement, the museum’s first exhibit is a dense stacked wall of rifles—all pointed right at you.

The Norwegians were part of the war before occupation. Their extensive merchant marine industry aided the Allies at sea, and people guarded the ports and cities at home. The country’s treasure of gold bullion was shipped away to safety and other such precautions were taken. For an excellent look at the tumultuous first three days of the war in Norway, watch The King’s Choice, which was a Norwegian entry in the Academy Awards.

Sinking a German ship

Once Poland had been invaded on Sept. 1, 1939, the Norwegians knew the Germans would soon come, and their defenses were heightened. On April 9, 1940, the Germans moved ships toward Oslo to begin their invasion. The first one, however, the cruiser Blücher, met its fate as Norway’s ready guns boomed across Oslofjord, and an accompanying cruiser was also crippled. This action delayed the invasion a crucial twelve hours, giving Norway’s parliament and its royal family the chance to escape the capital and direct continued fighting as they fled north.

In the early days of the war, the Allies battled with the Germans in Scandinavia, considered a crucial location for Germans to launch further into Allied territories. The loss of German ships in those northern battles were considered to have significant effect later in the war.

That first German warship still lies far below the fjord’s cold waters, but the Blücher’s anchor is on defiant display by the city’s Aker Brygge ferry terminal, just across from a statue of a fighter in the country’s resistance movement who was a key figure in sabotaging many other ships that anchored nearby during the occupation.

On a lunchtime walk with Jan Roll we learned the stories of these monuments, and our understanding and respect would be deepened with our later visit to the Resistance Museum.

The story of Norway’s government during the war is an extensive tale that I will just touch on here. In early June 1940, King Haakon VII, the royal family and the cabinet escaped by boat to exile in England, and a puppet government was headed by a Norwegian man named Vidkun Quisling, who had been cooperating with the Germans.

A spirited resistance

Meanwhile, as we learned in the excellent museum, Norwegian resistance began. Battles were fought on land and sea.

Official organizations in Norway refused to cooperate with the Germans. National sports organizations went on strike, the Norway supreme court resigned, and many other groups issued statements of defiance against the suspension of constitutional rights. Church leaders, professors and teachers all protested and many of them stopped work. At great risk, the extensive merchant navy, which had a presence in seas around the world, continued to secretly shuttle supplies to Great Britain.

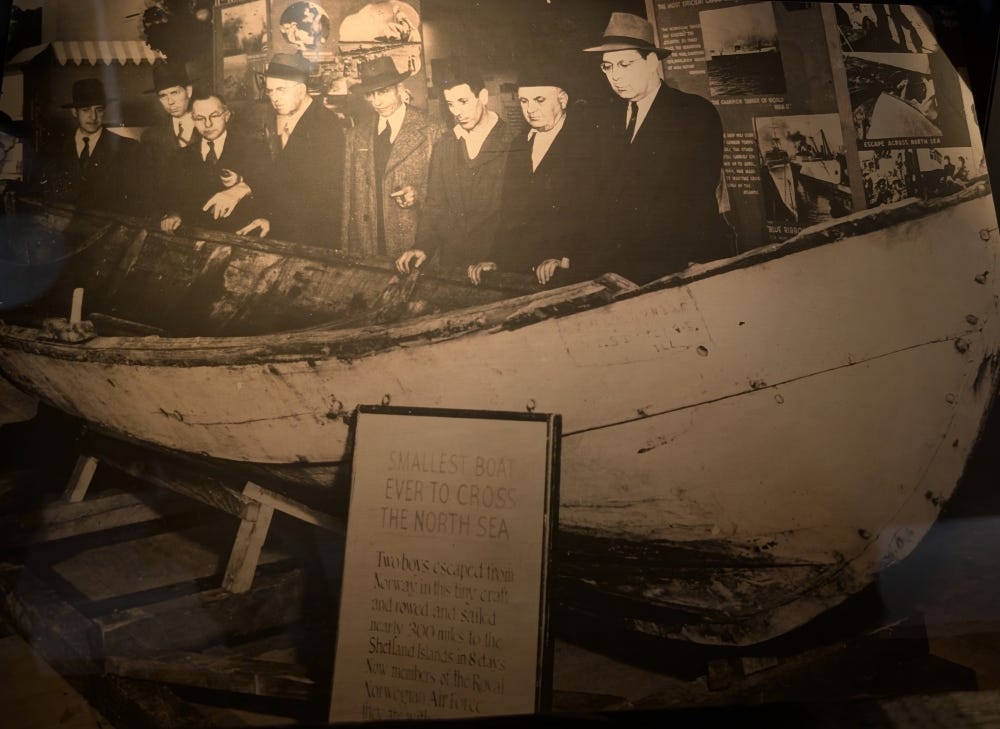

The museum also told of individual feats, including one that echoed Finn Roll’s daring escape. A photograph showed “the smallest boat ever to cross the North Sea,” sailing 300 miles to the Shetland Islands in eight days, after which the two boys sailing it joined the Royal Air Force and fought in the skies over France.

However, the museum also told of a sobering toll extracted by the rough sea voyage. More than 3,000 people tried to escape to Great Britain in small boats, and more than 300 died in the attempt.

A steady stream of small boats, called fishing smacks, made the sailing that came to be called “the Shetland Bus.” They were replaced in 1943 by three ships on loan from the U.S. Navy.

The resistance was declared illegal by German occupiers, which the fighters wore as a badge of honor. If discovered, however, they were harshly punished. One gallery wall showed “The Three Patriots,” men who had been executed on the grounds right outside the museum. These men and others shown in the museum were not named, a purposeful step to honor all who took part in the war effort by not elevating a few.

Clandestine newspapers were printed to share resistance details, on penalty of death if caught. Homemade radios were built and hidden away, in things like books and birdhouses.

As the resistance became more sophisticated, they even manufactured their own guns and other weapons.

In the first two years, over one thousand resistance fighters were sent to prison, and two hundred died.

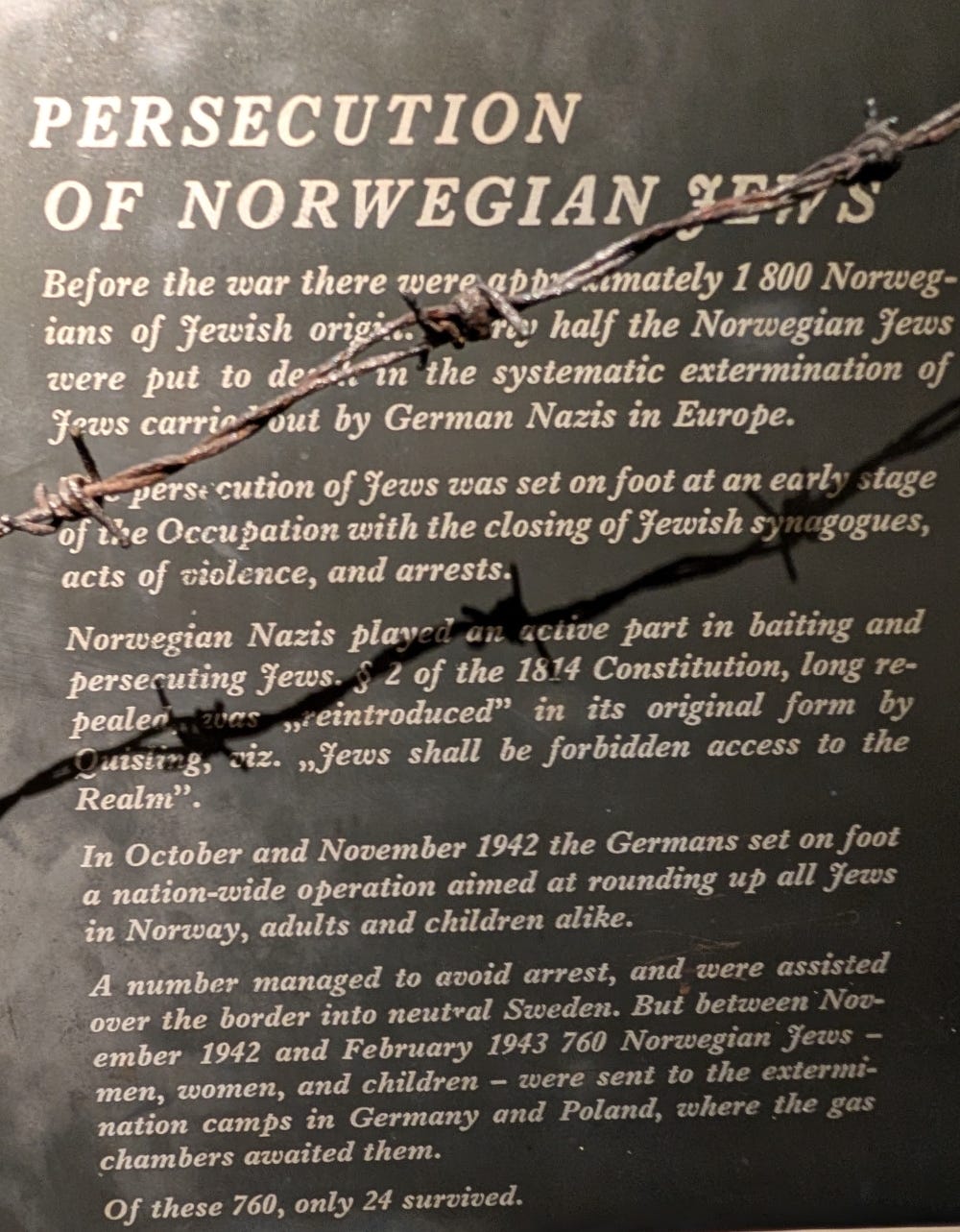

All told, the Germans imprisoned over 40,000 Norwegians, so many that they had to set up prison camps, the largest of which was on the outskirts of Oslo and housed nearly half of the prisoners. As horrible as were those camps, even worse conditions existed in Nazi camps set up for their eastern European and Russian prisoners. It’s estimated that more than 100,000 were imprisoned there, and 17,000 bodies were found in mass graves after the war. It was equally grim for Norwegian Jews. Most who were caught were sent to German concentration camps, where more than 700 were killed.

Neighboring Sweden was officially neutral, which enabled some Norwegians to take refuge there, and eventually begin to support the resistance movement and to form Norwegian army units. Toward the end of the war, this trained force, ultimately numbering 13,000, took part in reclaiming the country.

By the end of the war, the resistance and an organized corps called the Milorg fielded 40,000 fighters. The Milorg was named an official branch of the Norwegian military.

Honoring a Resistance hero

Although the museum kept its heroes namless, I knew of one man whose efforts stood above all others. Known during the war as Agent No. 24 or “Kjakan” (which translated to “The Chin”), Gunnar Sønsteby would become famous and his exploits legend. His resistance efforts sounded a bit familiar: he skied and parachuted into the fray. He was a leader of the underground press, became a master of disguise, and was nabbed by the Gestapo but escaped. His “Oslo Gang” would blow up ships and munitions stores, and were eventually called the best group of saboteurs in Europe.

According to Wikipedia, Sønsteby, who was from Rjukan, became “the most highly decorated citizen in Norway, including being the only person to have been awarded the War Cross with three swords, Norway's highest military decoration.” The lengthy account also notes that in 2008 he was the first non-American awarded the United States Special Operations Command Medal. Another famous recipient of that award was Robert T. Frederick, commander of the First Special Service Force.

One more Sønsteby connection significant to my father’s unit and that other famous Norwegian: On the cover of a recently published book about Finn Roll, A Norwegian in the Devil’s Brigade, a quote appears from the famous Agent 24: “You know, what I did during the war was nothing compared to what Finn did.”

A documentary on Finn Roll is in production and will be shown on Norwegian television this fall.

One final note: although the Force was never deployed against the German efforts to produce heavy water for their bombs, I learned that the Norwegians, with help from Britain, attacked the Rjukan plant four times in raids that sometimes failed but also crippled the plant or destroyed supplies of the crucial material. In 1943, their sabotage caused heavy water production to shut down for three months.

Watch “Number 24,” the new movie about Gunnar Sønsteby:

Read The Winter Fortress: The Epic Mission to Sabotage Hitler’s Atomic Bomb by Neal Bascomb, which historian Douglas Brinkley called “A riviting, high-action World War II thriller with nothing less than the fate of planet Earth on the line.”