'Marley was dead.' Yeah, but still a delightful read

The Dickens classis 'Christmas Carol' is best in text

As a Christmas treat, I want to share a bit of Dickens with you. Please pause your holiday festivities for a few minutes to read this. (Or you can listen, but bear with me; I’m still experimenting with audio.)

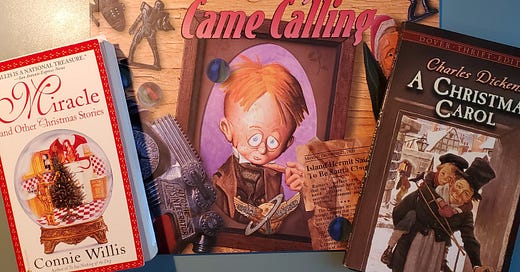

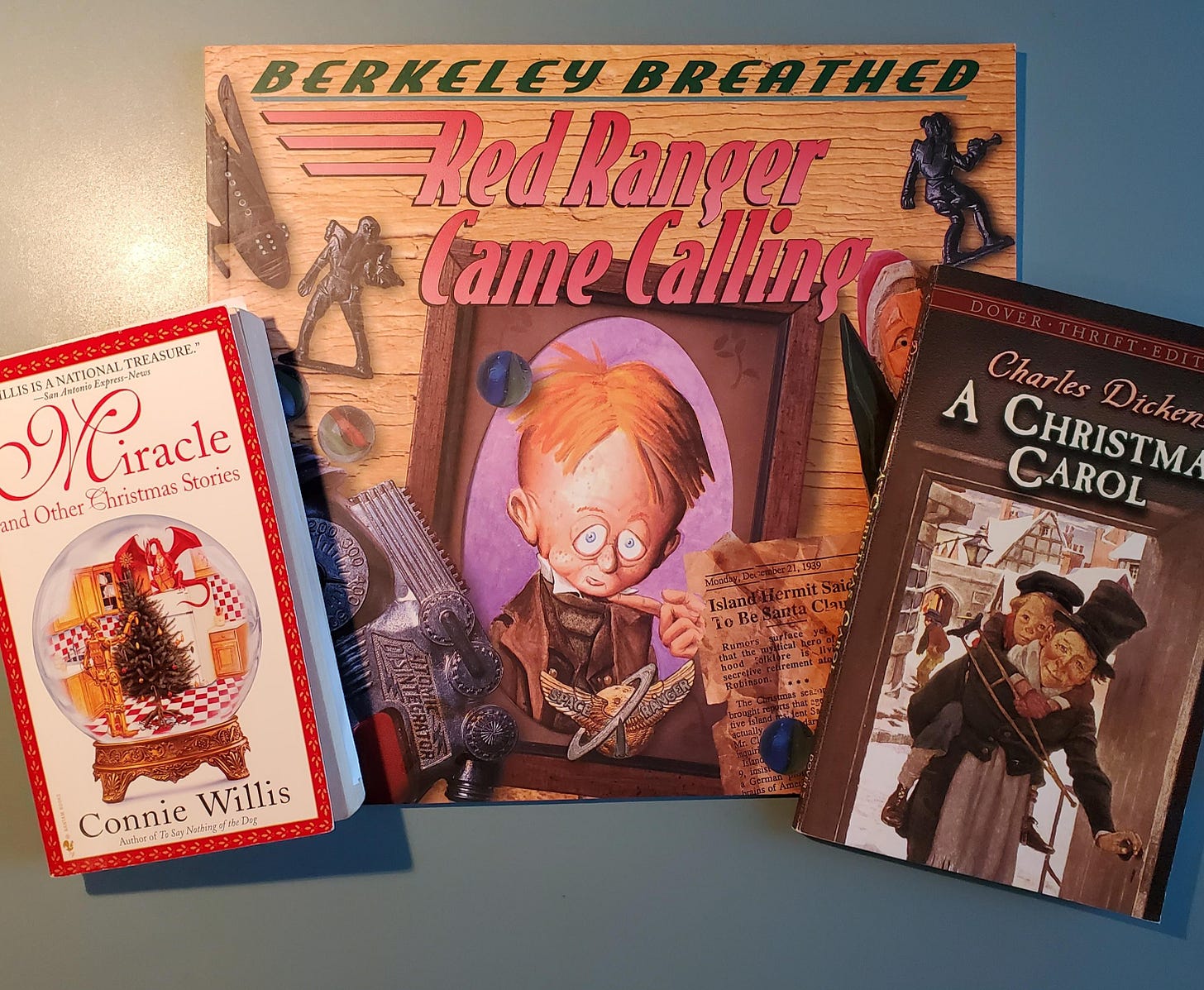

Christmas books tumble out of our decoration boxes each year, and I love to just grab one and read a bit, even though I’ve read them all many times.

Connie Willis’s short story collection “Miracle,” coming from the fertile mind of one of our greatest sci-fi writers, is delightful. She blends fantasy, science fiction and everyday holiday magic in heartwarming ways.

Berkeley Breathed’s “Red Ranger Came Calling” is a wonderful illustrated story by the creator of the classic “Bloom County” comic strip. It’s the story of a boy who fashions himself the Red Ranger and has a simple request for Christmas: “an official Buck Tweed Two-Speed Crime-Stopper Star-Hopper Bicycle.” Indeed. Who wouldn’t want that?

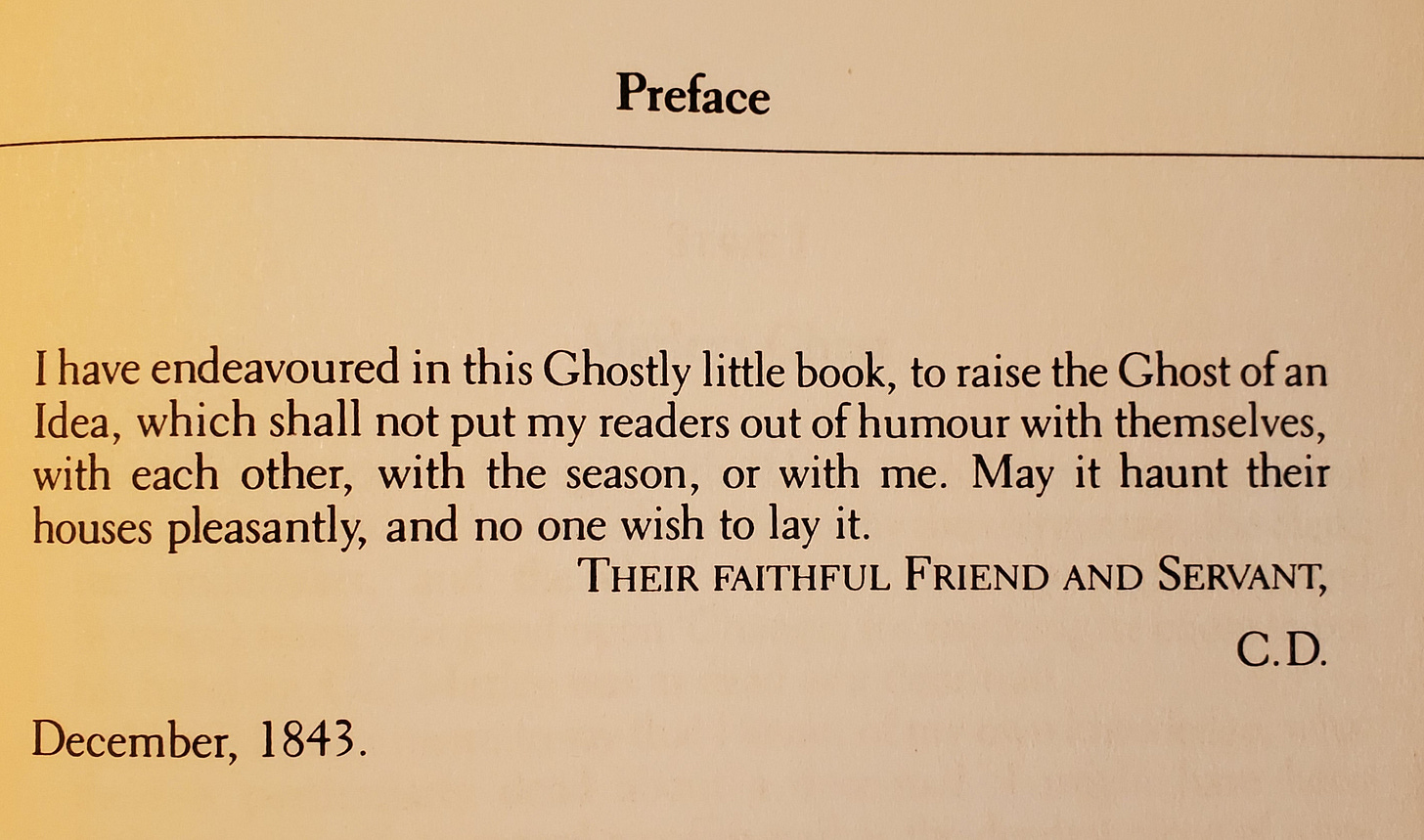

If I pass by those, though, inevitably I’ll flip open the all-time holiday classic “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens. Of course I’ve seen it many times on stage and screen, probably even heard it as a radio play, but reading the original, published in 1843, provides a much deeper vision of Dickens’s characters and story. His use of language is masterful. Let me show you—here’s the first five hundred words, in the original, complete with random capitalization and odd punctuation.

Stave 1

Marley’s Ghost

Marley was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt whatsoever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it: and Scrooge’s name was good upon ’Change, for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was dead as a door-nail.

Mind! I don’t mean to say that I know, of my own knowledge, what there is particularly dead about a door-nail. I might have been inclined, myself, to regard a coffin-nail as the deadest piece of iron-mongery in the trade. But the wisdom of our ancestors is in the simile; and my unhallowed hands shall not disturb it, or the Country’s done for. You will therefore permit me to repeat, emphatically, that Marley was dead as a door-nail.

Scrooge knew he was dead? Of course he did. How could it be otherwise? Scrooge and he were partners for I don’t know how many years. Scrooge was his sole executor, his sole administrator, his sole assign, his sole residuary legatee, his sole friend and his sole mourner. And even Scrooge was not so dreadfully cut up by the sad event, but that he was an excellent man of business on the very day of the funeral, and solomonized it with an undoubted bargain.

The mention of Marley’s funeral brings me back to the point I started from. There is no doubt that Marley was dead. This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful can come of the story I am going to relate. If we were not perfectly convinced that Hamlet’s Father died before the play began, there would be nothing more remarkable in his taking a stroll at night, in an easterly wind, upon his own ramparts, than there would be in any other middle-aged gentleman rashly turning out after dark in a breezy spot—say Saint Paul’s Churchyard, for instance—literally to astonish his son’s weak mind.

Scrooge never painted out old Marley’s name. there it stood, years afterwards, above the warehouse door: Scrooge and Marley. The firm was known as Scrooge and Marley. Sometimes people new to the business called Scrooge Scrooge, and sometimes Marley, but he answered to both names: it was all the same to him.

Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone, Scrooge! A squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching covetous old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster. The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait, made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice. He carried his own low temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dog-days; and didn’t thaw it one degree at Christmas.

. . .

See what I mean?

Post Script: I must also recommend a wartime classic, “Maquisard: A Christmas Tale,” by Albert J. Guerard. Published in 1995, it’s a true tale of a few weeks the author spent in December 1944 with the French forces in Cognac in southwest France. The author says his novel is closely based on experience, is “an affectionate recollection of a number of persons who met every day in a small café, where they huddled over the wood stove and drank cognac to shut out the cold and shut out too the traumatic memories of friends and families, wives and children lost or imprisoned, tortured or killed by the German occupier.” And it’s a heartwarming tale of an American soldier who, on his way home to his own children, helps out the villagers by escorting four orphans to Paris. Find a copy and treasure it.

And if you want someone to read you another story, here’s “Red Ranger Came Calling” on YouTube:

Thanks for reading to us, Bill. The story was more interesting in your voice. I, too, have read or seen so many versions of A Christmas Carol, but I think your reading (even though it was only an excerpt) was my favorite.

You should narrate more of your posts.