Catacombs and Pyramids

Spending Halloween among the dearly departed

Our steps reverberated on vast marble slabs as we hurried along the echoing colonnade leading to the massive church. Traffic flowed by on the slick, black pavement of the adjacent road and pigeons banded along the gutter, pecking the still air. Our destination lay at the end of the portico, burnished wood panels centered with oversize handles and clasped by massive hinges. Susie and I were about to enter the catacombs.

Once below, that it was early morning meant nothing. Among the hushed concrete hallways, time was immaterial, because the residents no longer marked the earthly world. Schedules, appointments, clocks, meal times, even sleep were all worthless—constructs for human consciousness. What is left of the body, and the mind, laying in eternal rest, is but a memory and a few square feet of corporeal material. Lowly peasant to high priest, famed leader or poet or mathematician—yes, even brilliant scientist—becomes simply a piece of the earth slowly returning to its constituent elements.

But among the silence and the former selves, we spied a velvet rope cradled by golden stanchions, beyond which was a figure robed in white and red, kneeling on the cold stone. It seems that all are not alike in death. Some are more revered.

The priest was flanked by a fabric wall in similar colors, which upon closer inspection was a group of fellow priests, eyes down and hands drawn in, respecting the prayer being offered to the man-sized slab of marble commanding the arched niche along this catacomb walk. In the soft glow a plaque shone just enough to reflect the writing: John Paul II. We had come upon the grave of the most beloved Catholic pope of our era, at rest far below the grand edifice of Saint Peter’s Basilica.

It was All Hallows Eve, the day preceding All Saints Day, and we chose to mark that morning on our Roman holiday with a visit, prior event to breakfast, to Vatican City’s most famous dead. It seemed a fitting way to start Halloween.

We stood among the former popes. A great many of them are entombed in St. Peter’s catacombs. But we also stood on—or rather one floor above—the burial ground’s most famous resident, Saint Peter himself, who is said to have been buried in the necropolis. Mere tourists, and most other souls on earth, are not allowed entry into that hallowed space.

Slowly we made our way through the hushed environment, stopping at each arched, lit grotto to view the name of its inhabitant and the embellishment on his marble sarcophagus or the walls around the tomb.

On a previous day we had braved the long lines of tourists and pilgrims to visit the Basilica itself, gawking at the soaring dome in the distance above our heads, beyond the layers of plaster encased in gold and seemingly endless panels of saintly painted scenes. We moved through the complex to view the history and art and sculptures in gallery after gallery, finally entering yet another slow-stepping line into the Sistine Chapel to again crane our necks to view a masterwork.

So much to see, too much to appreciate in just one day. Our next visit, then, was to see what eluded us on the previous one: the high and the low. Beginning at dawn in the catacombs allowed us to simply walk through the doors with a small group of visitors, the only others who struggled out at such an early hour. After thoroughly touring the basement, we returned to the light and ventured as far as we could without divine help in the other direction: we ascended to the roof.

On the way we climbed a set of claustrophobic passageways and flight after flight of stairs to the inner edge of the domed roof. From that vantage point we were nearly level with panel after panel of gilded images of angels, in gauzy robes and backed with wings. Their shapes seemed odd, which we deduced were because the artists foreshortened the forms to make them look natural from the basilica floor.

Rows of blue stars and gold flourishes circled into the recesses of the cavernous ceiling, bolstering the awe that is felt when viewing such a grand architectural and artistic achievement.

We then continue above the dome, yes, right to the roof of this amazing edifice. Again, the scale was boggling. A line of statues faced away from us, but of course they cast their gaze over the vast plazas of St. Peter’s. Saint after saint stood against the blue sky with Jesus, the largest statue, at the center.

The whole of Rome lay before us, from Castel San Angelo to the piazzas to the warren of streets comprising neighborhoods that had housed Romans for thousands of years. The Tiber River cut a serpentine ribbon through the ancient city.

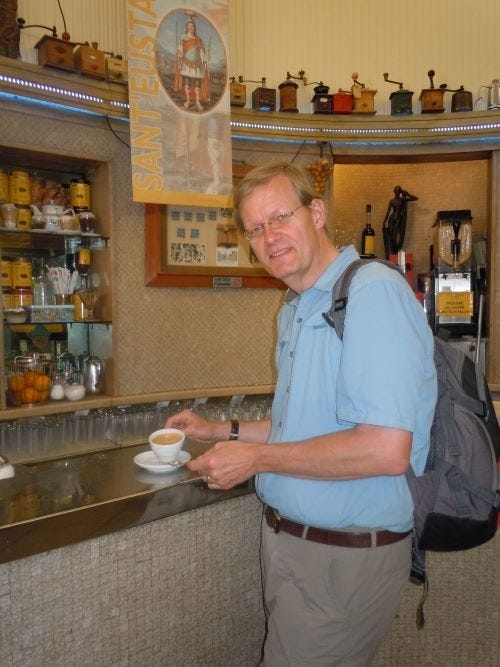

Difficult to conceive anything that could top our early morning outing, but we descended to earth and set off in search of breakfast. Near enough sat my favorite Rome coffeeshop, Sant’Eaustachio il Caffé, and we stepped over the blue stag set in tile at the door to procure their ultra-creamy espresso.

We filled the day outdoors, continuing to fuel ourselves along the vialles and panetterias of the old city. We were thankful for a cool, overcast fall day and a lighter than normal crush of tourists.

As the afternoon waned, we wondered if the Romans would observe Halloween the way we see it at home, with flocks of little ghosts and goblins and superheroes running house to house and begging for candy. We’d seen a few costumes, but it seemed mostly in the touristy shops.

So we decided to end the day as we’d begun, among the dead.

Rome is the most Catholic of places, naturally, so there is only one Protestant cemetery in the city. You can reach it by venturing into the city’s Metro and finding your way to the Pyramide stop on the subway line that runs south of the center city. The stop is named for the unmistakable landmark and surely one of the most unexpected structures in this ancient Italian city. Yes, a pyramid. One side faces the Porto San Paolo, a gate to the city dating to 275 AD, and another side faces and forms a border for the burial ground called Cimiterio Acattolico, which translates as Non-Catholic Cemetery.

The pyramid was actually built not by Egyptians, but by ancient Romans, as a tomb for Gaius Cestius, head of a religious order. At the time of its concrete and brick construction it had been outside the city, but as the city expanded they used it as part of the defensive wall.

Skirting the pyramid and the ancient city gate, we entered the Protestant Cemetery a little before dusk. There, as we suspected, Halloween was being observed. Skeletons with flesh beneath their fabric masks were darting among the gravestones, while the pointed top of a witch hat waggled over a marble tomb. Along the narrow walkways we met a few small groups of revelers, but all were respectfully quiet, as befitting the somber location.

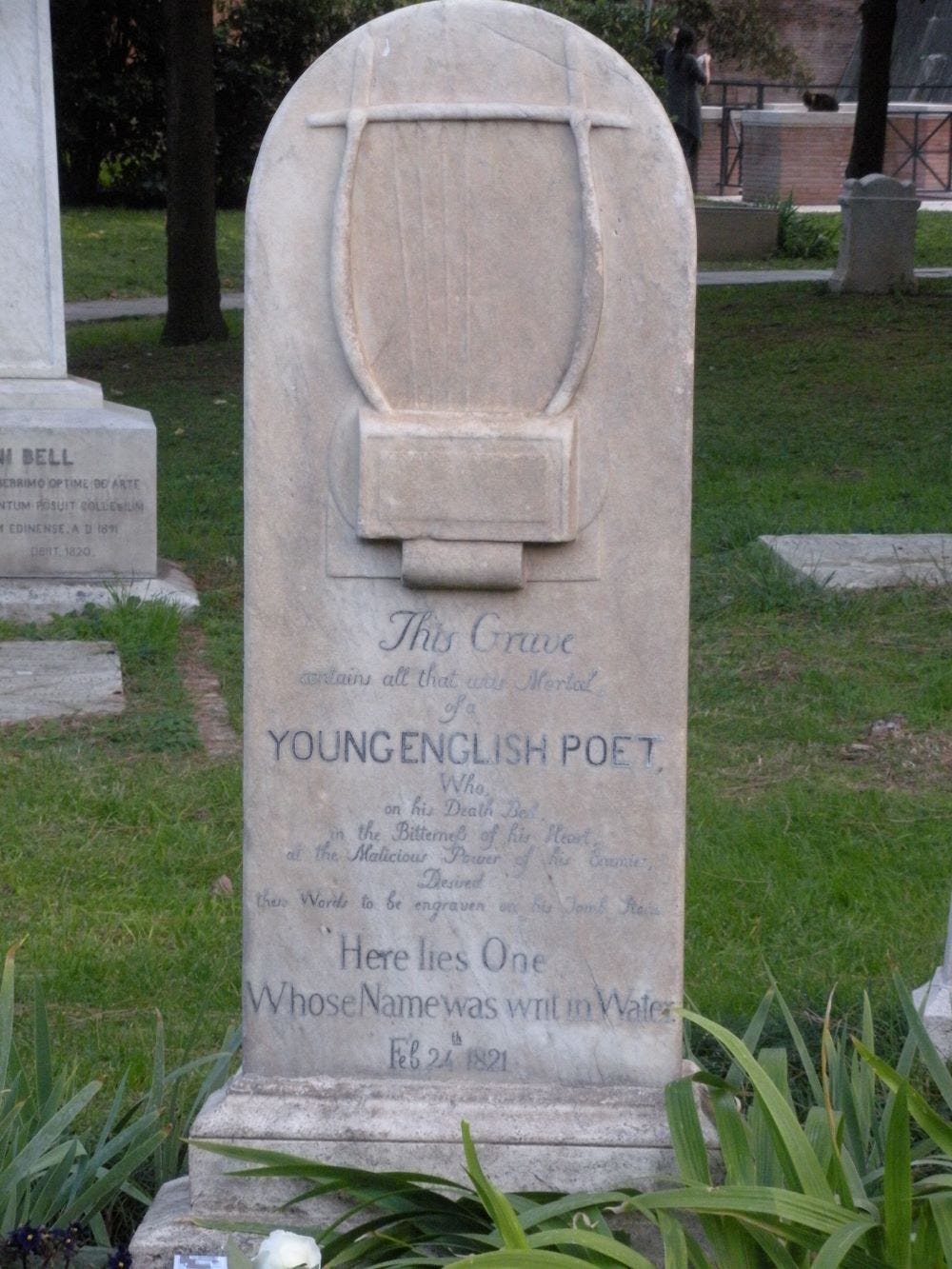

We also were there on a bit of a literary pilgrimage, because buried there are two of England’s most famous poets. In a far corner we found the grave of John Keats, the Romantic poet who in 1821 died young at 25 of tuberculosis. His grave carries one of the most touching phrases in all of burialdom, and also a bit of mystery. Under the image of a lyre with broken strings and some writing that describes him only as “a young English poet” is the phrase of his choosing: "Here lies One whose Name was writ in Water." And indeed, his actual name is not inscribed. I sang a silent birthday song to the poet, who was actually born on October 31, 1795.

We then went in search of his friend, Percy Bysshe Shelley who, although more accomplished and considered now to have been one of the Romantic movement’s leading lights, did not last much longer than his friend, dying a year after Keats, at age 29. Although his life too was plagued by illness, he was lost when his small boat capsized in a bad storm, and his corpse did not wash ashore until ten days later. I’d be remiss in this Halloween-themed tale if I didn’t point out that the poet’s wife, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, penned one of our most enduring monster stories: Frankenstein.

We finally came upon his headstone in a densely packed center section of the cemetery, and again were moved by the inscription. His name was indeed on the flat marble marker, but at the bottom were a few (appropriate yet ironic) lines from Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “Nothing of him that doth fade/but doth suffer a sea-change/into something rich and strange.”

Ashes to ashes, I guess, and dust to dust, even to a life lost at sea.

Honor the holiday in another way, with the fuzzy freaky new wave guitar stylings of The Dream Syndicate, circa 1984. This is: Halloween:

…and here’s a gratuitous scary holiday image:

Boo!

"Here lies One whose Name was writ in Water." He was wrong about that, of course. I love the stories you weave. The unexpected cameos by Keats and Shelley made my heart flutter and brought me back to UND and how a Poetry of the Romantics class had a lasting effect on me. Sort of my "how I learned to love poetry" moment. And, now, Keats's line "the poetry of the earth is never dead" is in my head like an earworm and seems right for your lovely words.